Greetings, dear readers. Nine years ago, we packed up our first trailer and took to living on the road, posting the first blog for this website, “pilgrimage to here”. That was December 2014 and in December, 2023, we made the decision to unhitch our second trailer one last time and settle (for now) in Las Cruces, New Mexico, retiring from our nomadic lifestyle. Like bookends on a library shelf, this decision delineates a shelf symbolically overflowing with a treasure chest of memories and experiences which tumble out of me as write to you today.

On December 4, 2023, we officially retired our beloved Airstream, T2, and purchased a brand new Grand Design Reflection trailer, now T3. Here is the moment caught for the archives as our living space more than doubled with the transaction.

In our first blog, in 2014, we chronicled the often gut-wrenching process of selling and then emptying our condominium in Keene, New Hampshire. We had been there for thirteen years, accumulating 900 books and stuff that became the contents of our 2,200 square feet of living space gathered over decades living, working, and raising our kids . Back in 2014, we imagined that we would travel around the country for six months towing our compact TrailManor travel trailer, before landing in Albuquerque, New Mexico, perhaps renting a little casita for a year. Our intention in 2014 was toward “learning how to travel lighter and discovering what was absolutely essential”. We trusted we would figure it out as we traveled down the road.

We got the 2014 intention part right, and we got the state of New Mexico right, but the in-between events were completely surprising and incredibly transforming. Three months into the travel, we knew that we knew we weren’t going to stop driving the country, even for Albuquerque. We were drawn to figuring out this nomadic lifestyle and its delicious freedom. From a practical point, we knew we needed another travel trailer more suited to long term living with essentials like a full bathroom with shower, a working oven, and comfortable beds. We needed a rig that was engineered to navigate the rigors of driving America’s highways which are in various stages of repair and disrepair. We needed a rig that could keep us comfortable through the variations of climate and weather. So we traded in the TrailManor for our beloved Airstream, T2. We traded in our Ford Escape for a Ford-150 truck and we turned right back around and headed west in June 2015.

Over the intervening years, clocking over 100,000 miles of towing T2, we went through one truck (retired our first Ford-150 with 190,000 miles back in 2022), and visited every one of the lower 48 states. We camped in over 400 campgrounds and missed camping in only 2 states – New Jersey and Delaware. We managed to visit a bakers’ dozen of national parks/monuments, wrapping up our epic pilgrimage in September 2023 in grand style finally getting to Monument Valley in the Four Corners.

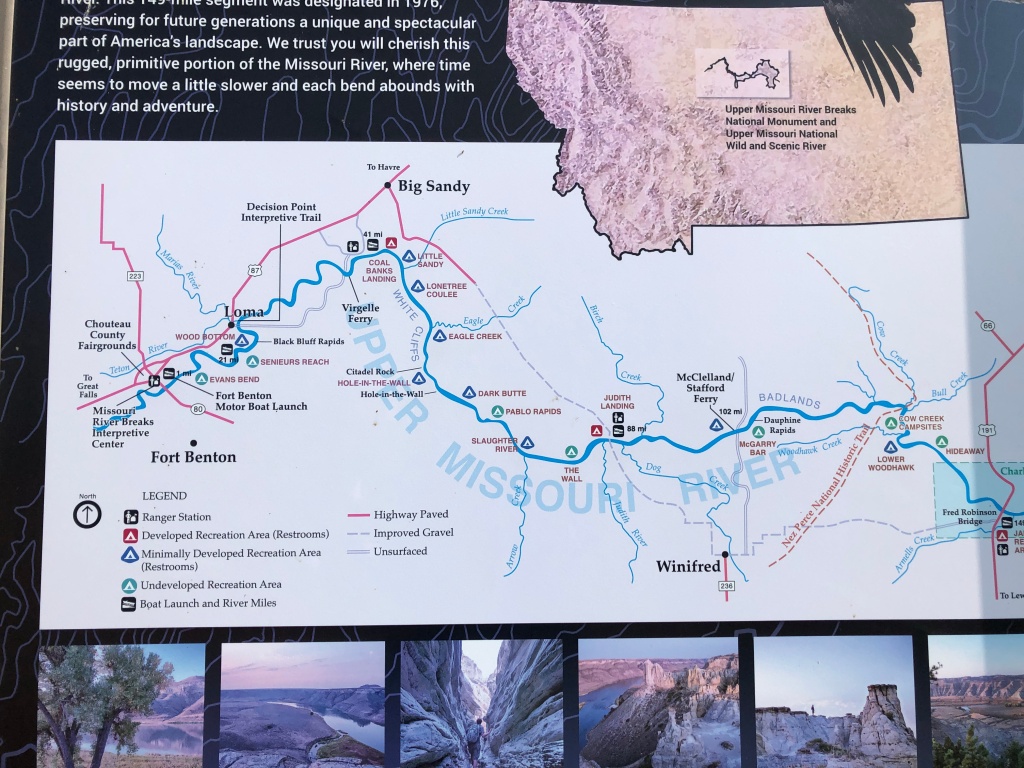

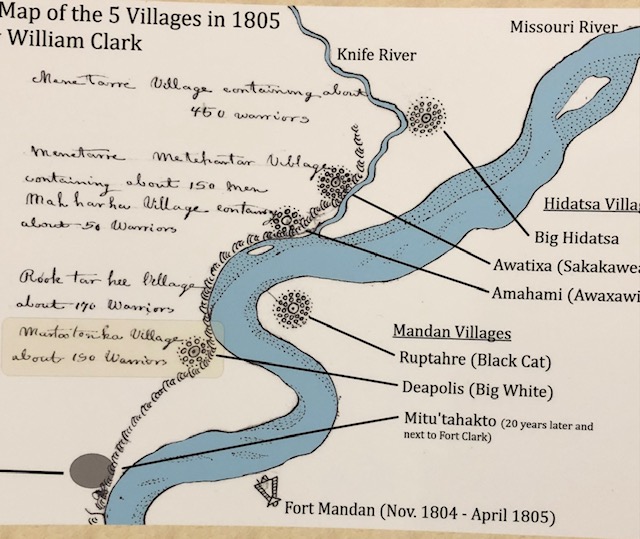

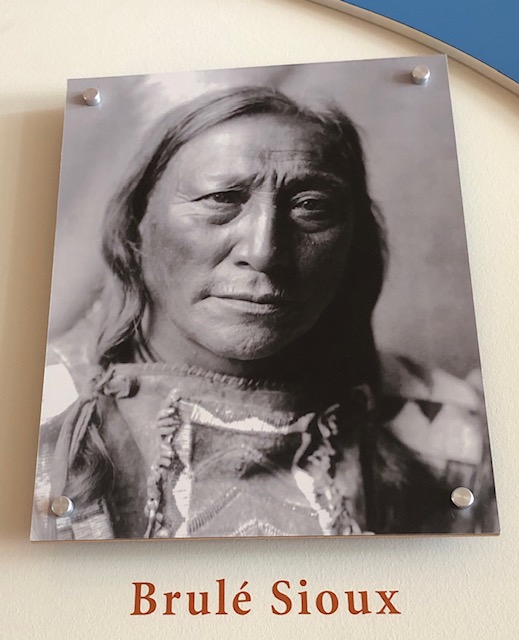

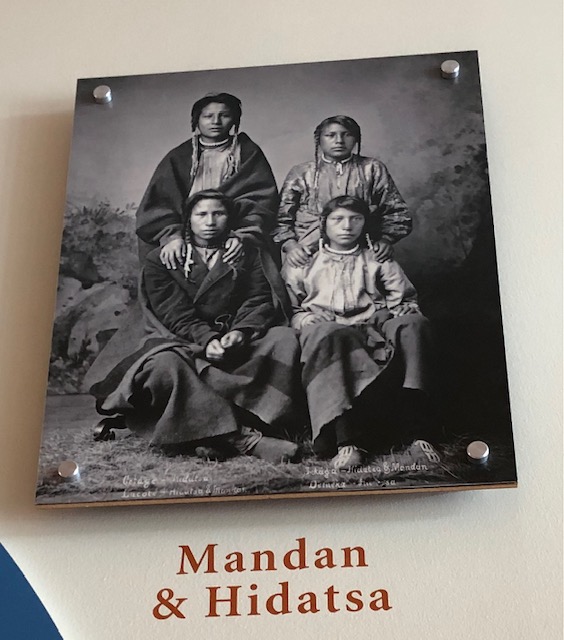

We made it to twelve of the official Presidential libraries, missing only Herbert Hoover and Gerald Ford. We manage to park on neighborhood streets and in really long driveways when visiting friends and family in Oregon, California, Montana, New York, Connecticut, North Carolina, New Hampshire, Florida, Texas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Ohio. We spent eight consecutive Septembers in our beloved Jackson, Wyoming at the iconic Gros Ventre Campground, unquestionably the most beautiful place we have ever parked our Airstream. Over two years in the 2020s, and guided by the genius of author and friend, Dayton Duncan and his classic work Out West, we re-traced most of the Corps of Discovery Expedition, Lewis and Clark’s journey from 1804 -1806. Starting in St. Louis and traveling to the Pacific Ocean, it captivated us both. In 2023, we booked a guided canoe trip on the remote Upper Missouri River, the one part of the Corps’ route accessible only by river, and rounding out this chapter of our life on the road, leaving us feeling blessed and deeply aware of the astonishing beauty and complexity of their accomplishments.

Along the way, we’ve had some memorable “OOOPS” experiences driving T2 where we probably shouldn’t have. There was the day we crossed the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, inhaling deeply inside the truck, hoping it would help T2 squeak through the travel lanes shockingly narrowed by those cement construction barriers. An error in map reading led us up the ridiculously perilous switchbacks on the back road from Jerome to Cottonwood, Arizona. We had some “Google map” moments, like the one in Louisiana where we were directed to turn onto “Pumpkin Patch Lane” (we didn’t).

We had freaky weather events including snow and hail at Davis Mountain State Park in Texas, and later, over Labor Day weekend in Wyoming. This latter one resulted in what I called our “snow-globe experience”. After six inches of heavy wet snow and wind, a tree limb broke off the cottonwood in our site, puncturing our bedroom skylight. Snow began falling inside our Airstream. This was the same storm where mountaineer-movie maker Jimmy Chin found himself stranded on a climb up the Grand Teton, so after learning about his experience, we were OK with our snow-globe moment, proving once again, it’s not what happens in life, it’s how one navigates it.

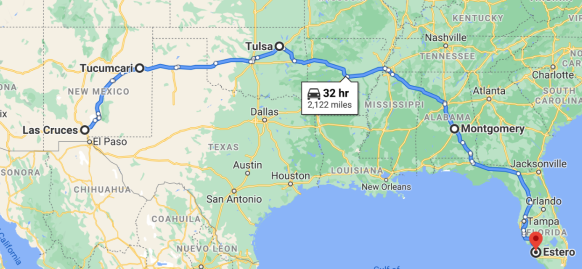

The blessings of our nine years in T2 are beyond words. The pandemic created unprecedented challenges for us all. We were volunteering in Florida in March 2020 when the shutdowns began. With 81million people living under shelter-in-place orders, and uneven quarantine restrictions, we had to re-do our entire travel. With some advanced planning and building up supplies (remember the days of toilet paper shortages?), we searched for places to camp as we prepared to leave Florida. Campgrounds were hard to find in Spring 2020, but KOA had a policy of staying open for long-haul truckers and RVs and we were able to get one night stays all across the country on our way to New Mexico. We learned how to live for weeks without going into grocery stores and then only when masked up. The remote campground check-ins were easy and a great accommodation. We filled up the gas tanks outdoors and without any interaction with people. Our Airstream became our mobile quarantine unit and we had no serious issues with the inconsistency of state-by-state regulations since we were just traversing the highways between one border and the next.

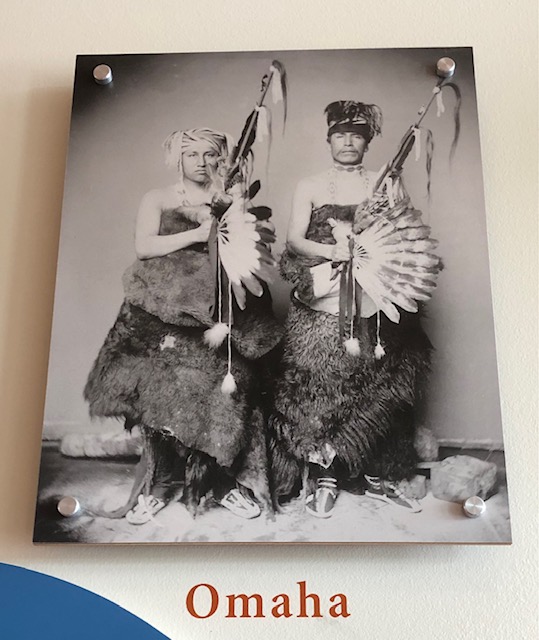

One year, 2016, was particularly memorable. It was the year when the engine in our one-year old truck developed a critical mechanical problem which turned into a 3-week entire engine rebuild in Bozeman, Montana. We were grateful for the generosity of friends who took us in and let us park T2 on their beautiful ranch just up the road from the Ford garage where they rebuilt the engine. It was the year of the devastating Berry Fire in Wyoming which destroyed over 200,000 acres in and around both Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks changing the landscape along Highway 89 forever. It was the year when Peter’s son, Davis, made the first of what has been annual trips to see us and we explored a new part of the West. That year, for ten days, we toured Mesa Verde National Park, Arches National Park, Canyonlands, Aztec Ruins National Monument, Jemez Pueblo in New Mexico ending up at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. In December, we drove east of the Mississippi to Florida. We had a reunion with California friends who flew to see us in Sarasota, Florida. And it was the first of our three-month winter volunteer gigs as docents at Koreshan State Park in Estero, Florida which ended in the 2020 pandemic.

2016 was the year when the engine in our one-year old truck developed a critical mechanical problem which turned into a 3-week entire engine rebuild in Bozeman, Montana. Peter’s son visited on our first national parks trips, here at Arches National Park. Friends visited from California. Our first residence in Estero, Florida at Koreshan State Park produced memorable photos and stunning sunsets on the beach.

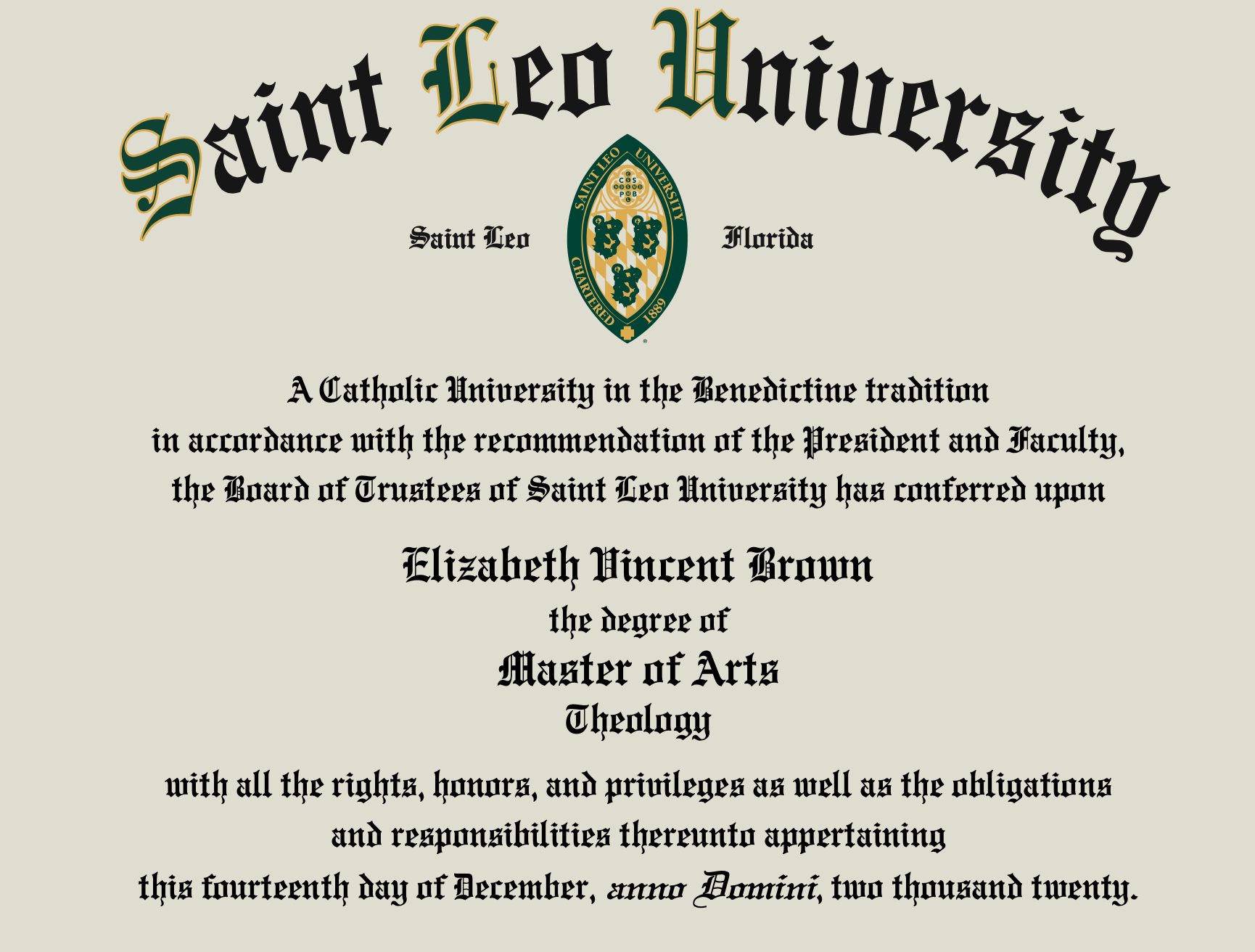

There were complete surprises that presented themselves. In March 2017, we happened to be at Death Valley National Park during the annual “Mars Fest”. It’s an annual collaboration among an alphabet-soup of organizations: NPS (National Park Service), NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), and a couple of other organizations who gather for keynote evening presentations, daytime guided hikes, and afternoon talks, centered on the general theme of the exploration of Mars. There were exhibits and lectures that were fascinating. One of my favorite talks was by Dr. Penelope Boston, NASA Astrobiology Institute, who is studying microbes living in mysterious places on earth, like crystal caves, caves full of pools of hydrogen sulfide, the ice fields of Antarctica, and deep ocean vents where no light is available. It was intriguing to hear what we are learning from studying life forms that would be helpful in understanding some of the possible life forms on Mars. That year (2017) was also the year when I decided to undertake a life-long dream of earning a Master of Arts in Theology. When I completed the requirements for the degree three years later, the pandemic was lifting and in 2021, I attended graduation at Saint Leo University in Florida. It marked the 50th anniversary of my undergraduate graduation from University of Connecticut and coincided with our oldest grandchild’s matriculation from the University of Vermont.

When I completed the requirements for the degree, in 2020, the pandemic was lifting and in 2021, I attended graduation at Saint Leo University, receiving my graduate degree. It marked the 50th anniversary of my undergraduate graduation from University of Connecticut and coincided with our oldest grandchild’s matriculation from the University of Vermont. It was also the time when I applied for, and received, my Portuguese citizenship.

In the early years of travel, we met some remarkable couples. Those friendships continue to enrich us today. One of the couples has since built a home along the Jemez River in New Mexico and we spent Thanksgiving 2023 with them. Another couple continues to travel like snowbirds from their Illinois home to Florida. This New Year’s we met up with them when we were visiting my son and his family in Tampa. Another couple continues to volunteer at Koreshan State Park and our holiday reunion in Florida was filled with laughter and happy conversations. In combination with our forever friends from the Triangle X Ranch in Wyoming, this love and those enduring friendships continue to enrich and transform us.

As I prepared this blog post, I uncovered something I wrote back in the winter of 2017 as we were preparing to leave our volunteer gig in Florida after that first season. It seems oddly prophetic and I’m including it here:

“We simply don’t get to see what lies ahead – in a marriage, in a volunteer job, in a cross-country trip, or in life. All we can do is show up every day … We don’t know how many days we will be tired, or worn down, or so exhausted and when that will feel like an insurmountable struggle. Uncertainty and mystery abide with faith in love. We leave here in just two weeks, transforming ourselves from resident volunteers with a single address back into pilgrims heading west, crossing the country with one and two night stops in our 2,300 mile journey west. The sunsets are calling us. Yes, every day I am falling in love with the life I have been given, all over again”.